How Much Money Do.you Have To Make To Have A Share Of Cost Of 816.0 Medicaid

Medicaid represents $ane out of every $6 spent on health care in the U.S. and is the major source of financing for states to provide coverage of wellness and long-term care for low-income residents. Medicaid is administered by states inside wide federal rules and jointly funded by states and the federal regime. Medicaid is a counter-cyclical plan, meaning that more than people become eligible and enroll during economic downturns; at the same time states may face declines in revenues making it hard to fund the country share. The health and economical furnishings of the pandemic have significant implications for Medicaid enrollment and financing. A companion information drove examines current fiscal and state acquirement data to assistance empathise how various economic factors that affect Medicaid are changing. This brief examines the following key questions about Medicaid financing:

- How does Medicaid financing work?

- How much does Medicaid cost and how are funds spent?

- What is the role of Medicaid in federal and state budgets?

- What are the implications of the pandemic on Medicaid and country budgets?

How does Medicaid financing piece of work?

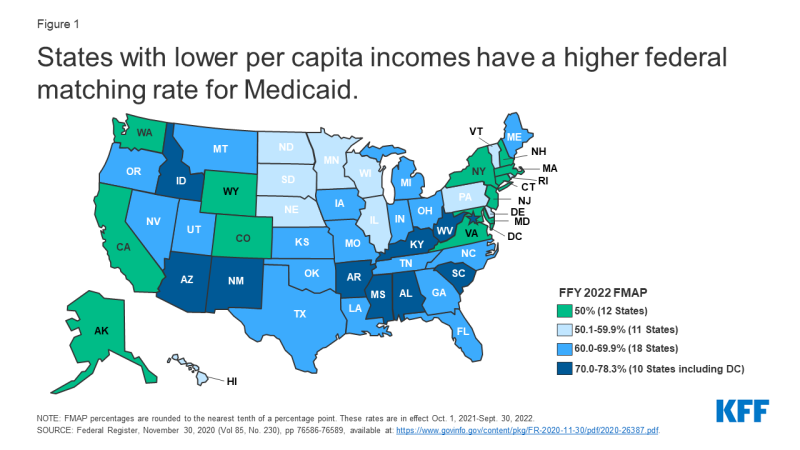

Under current law, Medicaid provides a guarantee to individuals eligible for services and to states for federal matching payments with no pre-fix limit. Medicaid provides an entitlement to eligible individuals. The federal government matches state spending for eligible beneficiaries and qualifying services without a limit. The federal share for traditional Medicaid (including spending for children, parents and not-ACA expansion adults, elderly and people with disabilities) is adamant past a formula set up in statute that is based on a state'due south per capita income relative to other states. The formula is designed so that the federal government pays a larger share of program costs in poorer states. Under the formula, the federal share (FMAP) varies by country from a floor of l pct to a high of 78 pct for FY 2022 (Effigy 1). States may receive college FMAPs for certain services or populations. In 2019, the federal government paid 64 per centum of total Medicaid costs with the states paying 36 percent. As discussed in more detail later, to provide financial relief to states and support Medicaid in response to the coronavirus pandemic, federal legislation authorized a temporary increment of six.2 percentage points in the federal match rate for traditional Medicaid spending for states that meet sure maintenance of eligibility conditions.

Figure 1: States with lower per capita incomes accept a higher federal matching rate for Medicaid.

To participate in Medicaid and receive federal matching dollars, states must come across core federal requirements .States must provide certain mandatory benefits (e.g., infirmary, physician, and nursing habitation services) to core populations (e.thousand., poor pregnant women and children) without imposing waiting lists or enrollment caps. States may too receive federal matching funds to cover "optional" services (due east.g., adult dental care) or "optional" groups (e.g., elderly with high medical expenses). States likewise have discretion to determine how to buy covered services (east.g., through fee-for-service or capitated managed care arrangements) and to prepare provider payment amounts. Based on program flexibility, spending per Medicaid enrollee varies significantly beyond states.

At that place are special match rates for the ACA expansion group, administration, and other services. While the standard FMAP applies to the vast bulk of Medicaid spending, there are a few exceptions that provide college match rates for specific populations and services including family planning, some new options to expand community long-term care services, and most notably people covered under the Affordable Intendance Human activity (ACA). The ACA provided 100 percent federal financing for those made newly eligible past the law from 2014 to 2016 (with that lucifer phasing down to 90 percent by 2020). The ACA originally required all states to implement the expansion of Medicaid to all people with incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty level, just a decision by the Supreme Court effectively made it optional. In general, costs incurred past states in administering the Medicaid program are matched by the federal government at a 50 percent rate. There are, all the same, some types of authoritative functions that are matched at higher rates such as eligibility and enrollment systems. Medicaid administrative costs in general represent a relatively small portion of total Medicaid spending (5 percent or less).1

Medicaid also provides "disproportionate share hospital" (DSH) payments to hospitals that serve a large number of Medicaid and depression-income uninsured patients. two DSH payments totaled $17.7 billion in FFY 2019. While states accept considerable discretion in determining the corporeality of DSH payments to each DSH hospital, federal DSH funds are capped for the state and besides capped at the facility level. Based on the supposition of increased coverage and therefore reduced uncompensated care costs under the ACA, the law chosen for a reduction in federal DSH allotments starting in FFY 2014. The cuts have been delayed several times and are currently set to take result in FFY 2024.

Unlike in the 50 states and D.C., annual federal funding for Medicaid in the U.Southward. territories is subject to a statutory cap and fixed matching charge per unit .Nevertheless temporary relief funds, in one case a territory exhausts its capped federal funds, information technology no longer receives federal financial support for its Medicaid plan during that fiscal year. This places additional pressure level on territory resources if Medicaid spending continues beyond the federal cap – making the constructive match rate lower than what is set in statute. Over time, Congress has provided increases in federal funds for the territories broadly and in response to specific emergency events. The allotments for each of the territories for FY 2020 and FY 2021 are approximately vii times the statutory levels every bit a result of additional funding added in the FY 2020 appropriation parcel and the Families First Coronavirus Response Deed (FFCRA). In addition to increased federal funding, the traditional territory FMAP of 55 percent was increased to 82 percentage for Puerto Rico and 89 percent for the other territories through FY 2021. Unless Congress acts, in that location will be a major financing cliff in at the end of FY 2021 for the territories.

How much does Medicaid cost and how are funds spent?

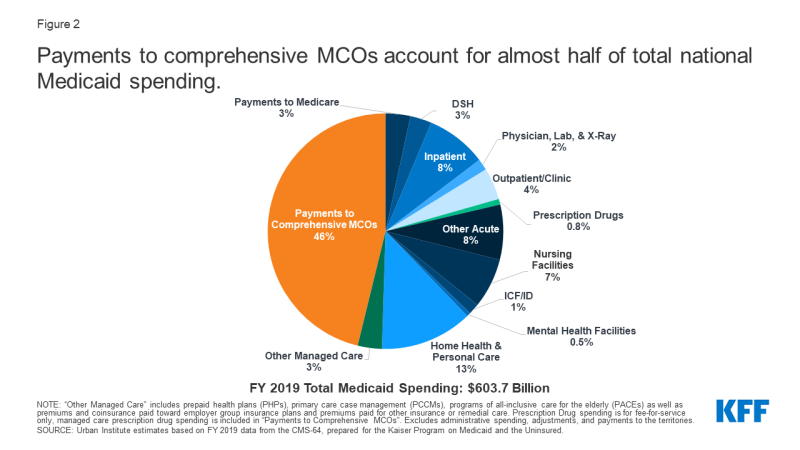

Capitated payments to Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) and for other Medicaid managed care (e.g., primary intendance case management (PCCM) arrangements) account for 49 percent of Medicaid spending. In FY 2019, Medicaid spending (not including administrative costs) totaled $604 billion. Managed care and wellness plans3 deemed for the largest share of Medicaid spending (49 pct) (with the majority of that share (46 per centum) representing payments to comprehensive MCOs), 23 percent of Medicaid spending is for fee-for-service acute care, 21 percent for fee-for-service long-term intendance, 3 percent for DSH, and 3 pct for Medicaid spending for Medicare premiums and cost-sharing on behalf of dual eligible beneficiaries (Figure 2).

Figure ii: Payments to comprehensive MCOs account for almost half of total national Medicaid spending.

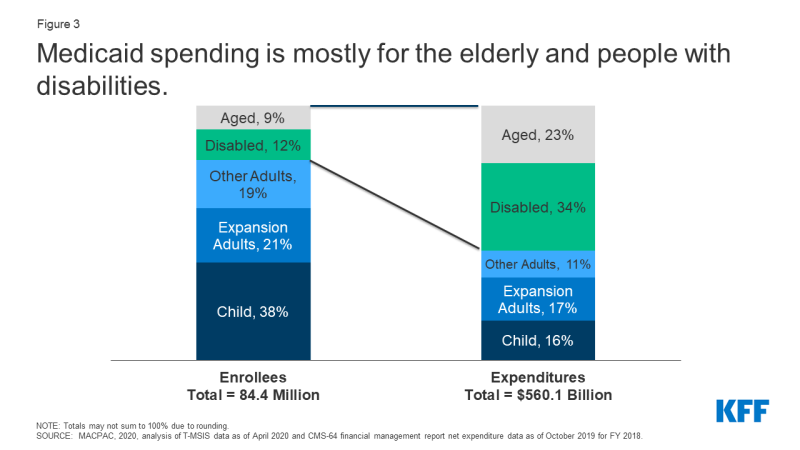

More than than half of all Medicaid spending for services is attributable to the elderly and persons with disabilities, who make upwardly ane in five Medicaid enrollees (Figure 3). Dual eligible beneficiaries – who are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid — account for nigh 34 percent of all spending. Although simply approximately 5.5 per centum of enrollees use long term services and supports, these enrollees business relationship for nearly one-third of all Medicaid spending on benefits.

Effigy iii: Medicaid spending is more often than not for the elderly and people with disabilities.

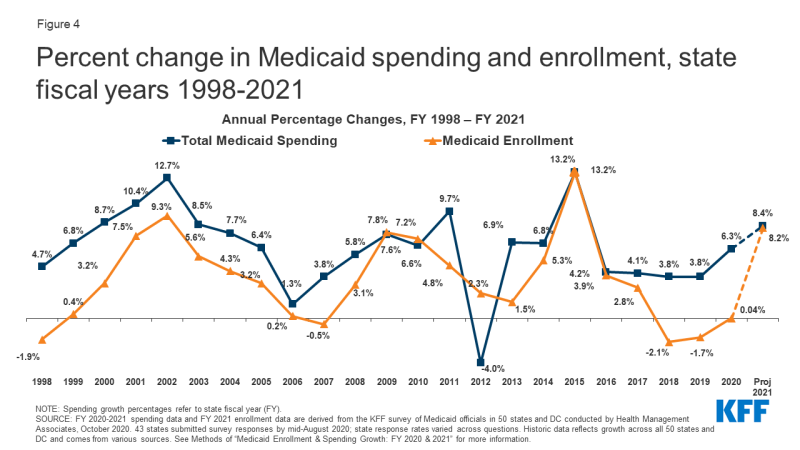

Medicaid enrollment and spending increases during recessions. Medicaid spending is driven by multiple factors, including the number and mix of enrollees, medical cost inflation, utilization, and state policy choices well-nigh benefits, provider payment rates, and other program factors. During economical downturns, enrollment in Medicaid grows, increasing state Medicaid costs at the same time that state revenue enhancement revenues are declining. Figure 4 shows peaks in Medicaid spending and enrollment in 2002 and 2009 due to recessions. Enrollment and spending also increased significantly following implementation of the ACA but have chastened in more recent years. Prior to the coronavirus pandemic which emerged in 2020, slower caseload growth helped to mitigate Medicaid spending growth in contempo years; all the same, higher costs for prescription drugs, long-term services and supports and behavioral health services, also as state policy decisions to implement targeted provider rate increases were factors states take recently cited as putting upward pressure level on Medicaid spending.

Effigy 4: Percent change in Medicaid spending and enrollment, state fiscal years 1998-2021.

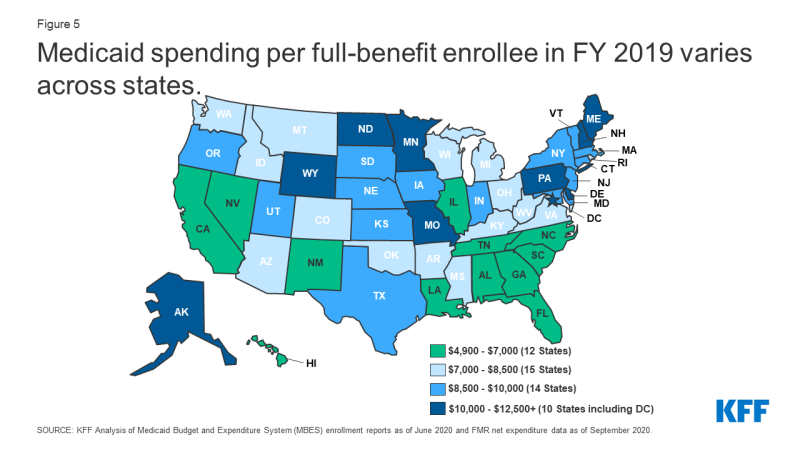

Based on current flexibility in the Medicaid plan, there is considerable variation in per enrollee costs across eligibility groups and across states. Total spending per enrollee ranged from a low of $4,970 in South Carolina to $12,580 in Northward Dakota in FY 2019 (Figure 5). Spending for the elderly and individuals with disabilities may be three to iv times greater than the spending for adult enrollees and more half dozen times spending for an average child covered by the plan. In improver, even within a given state and eligibility group, per enrollee costs may vary significantly, especially for individuals with disabilities.

Figure v: Medicaid spending per full-benefit enrollee in FY 2019 varies across states.

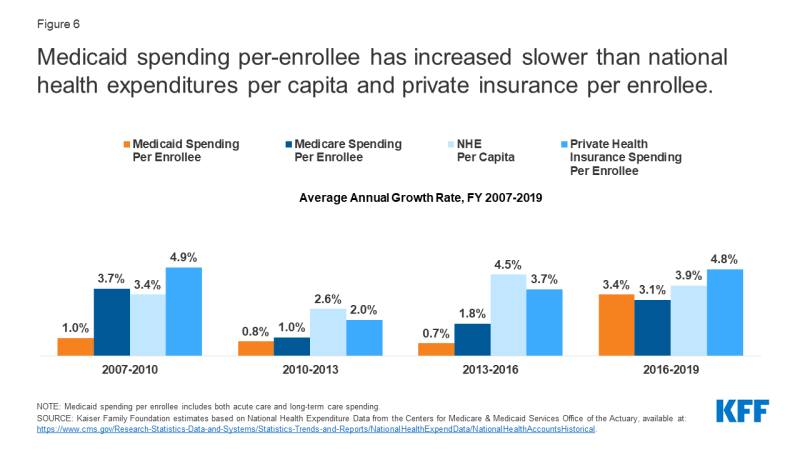

Medicaid growth per enrollee has been lower than individual health spending. Considering states share in the financing of Medicaid and states must balance their budgets annually, there is an incentive to constrain Medicaid spending. States may seek to control costs by restricting payment rates, controlling prescription drug costs, limiting befits and through implementing payment and delivery system reforms. Medicaid per enrollee spending grew slower than Medicare, national health expenditures, and private health insurance for all time periods from 2007 to 2016. From 2016 to 2019, while standing to grow slower than national health expenditures and private health insurance, Medicaid per enrollee spending grew slightly faster than Medicare (Effigy vi).

Figure 6: Medicaid spending per-enrollee has increased slower than national health expenditures per capita and private insurance per enrollee.

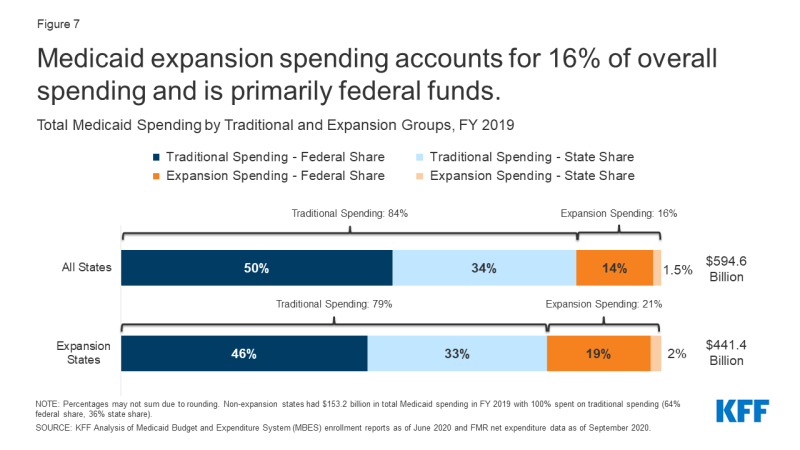

In FY 2019, spending for the ACA expansion group was $93.8 billion, with the federal government paying $84.9 billion of this cost. Overall, the expansion group represents 16 percent of overall Medicaid spending and 20 per centum of Medicaid enrollment. For the new adult expansion grouping, the vast majority of expenditures were paid for with federal funds (Figure 7). Later on receiving a 100 percent federal match rate for the expansion group for CYs 2014-2016, the federal share gradually phased down to 90 percent past January 2020.

Figure 7: Medicaid expansion spending accounts for 16% of overall spending and is primarily federal funds.

Prior to the pandemic, how did Medicaid chronicle to federal and state budgets?

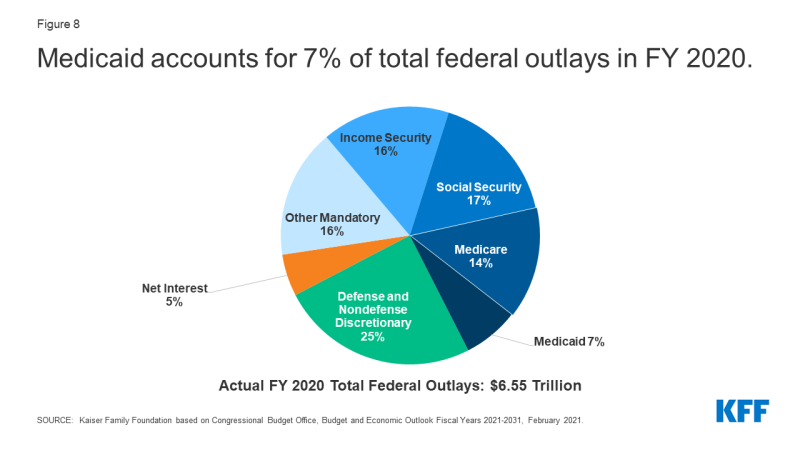

Medicaid accounted for 7 percent of all federal outlays in FY 2020, following spending for Social Security, Income Security, and Medicare (Figure 8). Medicaid accounts for a smaller share of federal spending than Medicare considering Medicaid program costs are shared by the federal regime and the states. Federal outlays for FY 2020 include large increases for unemployment bounty, primarily as a result of legislation that increased the benefit amount and the duration of the benefit besides as overall increases in claims due to the economic effects of the pandemic. Overall, federal outlays for income security increased from vii percent in FY 2019 to 16 percent in FY 2020. Federal outlays for Medicaid decreased from 9 percent in FY 2019 to 7 pct in FY 2020.

Figure 8: Medicaid accounts for 7% of total federal outlays in FY2020.

Medicaid is not just a spending item but also the largest source of federal revenues for state budgets. As a result of the federal matching construction, Medicaid has a unique function in land budgets as both an expenditure item and a source of federal revenue for states. Co-ordinate to data from the National Clan of State Upkeep Officers (NASBO), in SFY 2019, when looking at state spending from state and federal funds, Medicaid deemed for 29 percent of total state spending for all items in the state upkeep, but 16 per centum of all state full general and other fund spending, a distant second to spending on K-12 education (25 percent of country general and other fund spending). Medicaid is the largest single source of federal funds for states, accounting for more than than one-half (58 per centum) of all federal funds for states in FY 2019 (Figure nine). Due to the lucifer charge per unit, as spending increases during economic downturns, then does federal funding. During the ii economic downturns prior to the pandemic, Congress enacted legislation to temporarily increase the federal share of Medicaid spending to provide increased support for states to help fund Medicaid.

Effigy 9: Medicaid spending equally a share of total, state, and federal funds, bodily data FY 2019.

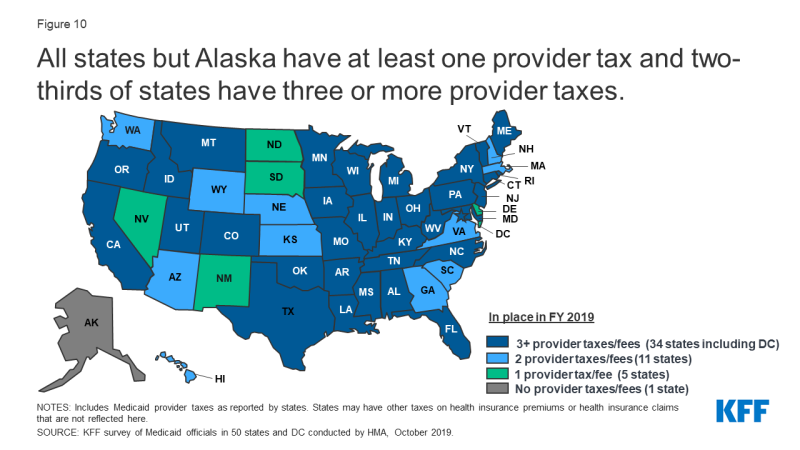

States tin can use provider taxes and IGTs (intergovernmental transfers) to assistance finance the country share of Medicaid. States take some flexibility to use funding from local governments or revenue collected from provider taxes and fees to assist finance the country share of Medicaid. All states (except Alaska) have at least one provider tax in place and many states take more than than three (Figure 10).

Effigy 10: All states simply Alaska have at least 1 provider taxation and ii-thirds of states have three or more provider taxes.

In responding to 2 major recessions prior to the pandemic, states adopted an array of policies to command Medicaid spending growth. During economic downturns, as Medicaid enrollment grows, states typically implement policies to restrict provider reimbursement rates and trim benefits. States may restore some restrictions when economic atmospheric condition meliorate. Overall Medicaid provider payment rates tend to exist lower than other payers. These lower payment rates have contributed to the programs relatively depression costs. In improver, states have implemented an array of strategies to control the costs of prescription drugs, and nigh states refine these policies each year. To address long-term strategies of cost control and coordinated care, many states take moved to implement a range of payment and delivery system reforms (such as alternative payment models or value-based payments) either using managed intendance organizations or other models.

Research shows that the influx of federal dollars from Medicaid spending has positive effects for state economies.Medicaid spending flows through a state'south economy and can generate impacts greater than the original spending solitary. The infusion of federal dollars into the country'due south economy results in a multiplier effect, directly affecting not only the providers who received Medicaid payments for the services they provide to beneficiaries, but also indirectly affecting other businesses and industries equally well. More recent analyses find positive effects of the Medicaid expansion on multiple economic outcomes, despite Medicaid enrollment growth initially exceeding projections in many states. Studies show that states expanding Medicaid under the ACA have realized budget savings, acquirement gains, and overall economical growth.

What is the issue of the pandemic on Medicaid spending?

The coronavirus pandemic has generated both a public health crisis and an economic crisis, with major implications for Medicaid, a countercyclical programme. To help support states as Medicaid enrollment grows and ensure continuous coverage for enrollees, the FFCRA authorized a half dozen.2 percentage betoken increase in the federal friction match rate for states that meet certain "maintenance of eligibility" (MOE) requirements. The boosted funds were retroactively available to states beginning January 1, 2020 and go along through the quarter in which the PHE menstruation ends. While the current PHE declaration expires 90 days from April 21, 2021, the Biden Administration has notified states that the PHE will likely remain in place throughout CY 2021 and that states will receive sixty days-detect earlier the cease of the PHE to let states time to prepare for the end of emergency government and the resumption of pre-PHE rules. Federal Medicaid outlays grew at a rate of 12 percent in FFY 2020 (over FFY 2019) compared to 5.2 per centum in FFY 2019 (over FFY 2018). This increment in the rate of annual outlays was largely owing to accelerated growth in the second half of the financial year reflecting the onset of the pandemic and the start of enhanced federal Medicaid funds in late March.

After relatively flat Medicaid enrollment growth in FY 2020 (0.4 percent), states responding to KFF's annual Medicaid Upkeep Survey conducted in June-August 2020 projected, on average, that Medicaid enrollment would increment 8.two percent in FY 2021 (over FY 2020) and total spending would increase by 8.four pct. Preliminary national data show that total Medicaid and CHIP enrollment grew to 78.9 million in November 2020, an increase of vii.7 1000000, or 10.viii percent, from February 2020. This growth likely reflects both changes in the economy, equally more people experience income and job loss and become eligible and enroll in Medicaid coverage, and the FFCRA MOE provisions that crave states to ensure continuous coverage for current Medicaid enrollees through the end of the calendar month in which the PHE ends. This growth represents a reversal of contempo Medicaid enrollment trends in 2016 through 2019, when the rate of total Medicaid and CHIP enrollment growth was declining or negative.

All states are experiencing fiscal stress tied to the pandemic, although individual land experiences vary.The impact of the pandemic on states depends on a variety of factors including the limerick of land economies, tax structures, virus manual levels, and country responses, among other factors. For example, states that are more dependent on tourism and the free energy sector have seen larger economical and state revenue impacts. Overall, however, land revenues declined in FY 2020, and greater declines are expected in FY 2021, resulting in the first full general fund spending subtract in enacted budgets in more than x years as states make reductions to meet balanced budget requirements. While the state fiscal relief provided by FFCRA has undoubtedly helped states avoid more astringent budget cuts, some states however face budget gaps that they must address. While states often turn to provider rate and benefit restrictions to constrain Medicaid spending during economic downturns, these cost containment approaches may not be equally viable with providers facing revenue shortfalls and enrollees facing increased health risks due to the pandemic.

The American Rescue Plan Human activity , the COVID-xix relief package that became law on March 11, 2021, contains a number of Medicaid-related provisions designed to increase coverage, aggrandize benefits, and adjust federal financing for land Medicaid programs. The police provides an boosted temporary fiscal incentive to encourage states that have non yet adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion to do so; a new option to extend Medicaid coverage for postpartum women from the current 60 days to a full twelvemonth for five years first Apr i, 2022, and a 10 percent bespeak increase in federal matching funds for Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS) for one yr outset on April 1, 2021. The law also eliminates the cap on prescription drug rebates that manufacturers pay to Medicaid in exchange for coverage of their FDA-canonical drugs on December 31, 2023, which is estimated to result in federal savings of $xiv.v billion. Finally, the new law provides $8.five billion in FY 2021 for provider relief fund payments related to COVID-19 to rural Medicaid, CHIP, and Medicare providers.

Looking Ahead

Medicaid spending and enrollment trends will go on to depend on the trajectory of the pandemic and the economic downturn, as well equally the duration of the PHE and the effects of the American Rescue Programme that became law on March xi, 2021. The temporary federal fiscal relief and continuous coverage requirements for Medicaid are tied to the duration of the PHE. The Biden Administration has notified states that the PHE will probable remain in place throughout CY 2021 and that states will receive sixty days-detect before the end of the PHE to allow states time to prepare for the end of emergency authorities and the resumption of pre-PHE rules. In add-on, the American Rescue Program includes a number of Medicaid related provisions designed to increase coverage, expand benefits, and adjust federal financing for state Medicaid programs. The new law also includes funds to help address the pandemic and provide additional fiscal relief to individuals and states.

Source: https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-financing-the-basics-issue-brief/

Posted by: hebertreveld.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Much Money Do.you Have To Make To Have A Share Of Cost Of 816.0 Medicaid"

Post a Comment